On the 30th of January 1933, the leader of the NSDAP, Adolf Hitler (link in Czech), was appointed Chancellor of the Reich by German President

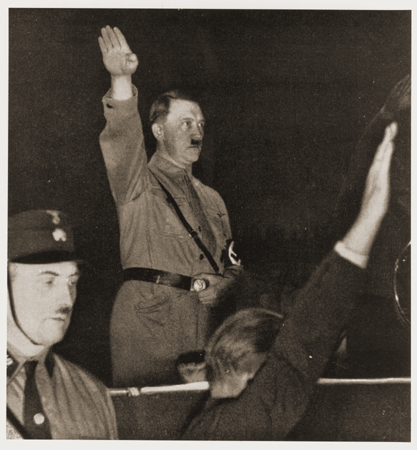

Hitler at a party meeting in February 1933. (Photo: Courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives)

At Hitler's wish, the Reichstag was dissolved and new elections were called. During the election campaign, on the 27th of February, there was a fire in the Reichstag building. Historians still disagree as to whether the fire was staged by the Nazis, or whether the arsonist who was arrested, the mentally-unstable Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe, was truly acting of his own accord. Either way, the Nazis cleverly used the situation for their own benefit. The next day, the government issued an urgent decree

(the Reichstagsbrandnotverordnung

) which - under the pretext of taking necessary measures against the communists - made major inroads into civil liberties. Limits were placed upon freedom of expression, assembly and association. It was also possible for secrecy of correspondence to be violated, house searches to be carried out with no court order, and property to be confiscated. From the legal point of view, the decree was de facto the equivalent of declaring a state of emergency.

Although the elections took place in an atmosphere of Nazi coercion and terror, the NSDAP did not manage to gain a majority of votes. It won with 43.9% of the votes, and only had a majority in the Reichstag with the aid of its conservative coalition partner, the German National People's Party, which had gained 8% of the votes. Despite the possibility of forming a government with majority support in the Reichstag, though, the Nazis decided to practically destroy parliamentary democracy. On the 23rd of March 1933, the Reichstag, under pressure, passed what was known as the Enabling Act, allowing the government to issue laws without the need for parliamentary approval. Only the Social Democrats voted against the law (the Communists had already been expelled from parliament.)

The process of Gleichschaltung (enforcement of conformity) in German society continued with a ban on the Social Democratic Party in June, and the "voluntary" disbanding of Zentrum, the Catholic party, in July 1933. In May, the trade union organisations were disbanded, and working people were required to join newly-created Nazi professional organisations. After the death of President Hindenburg in August 1934, Hitler effectively joined together the function of Chancellor and President, taking the title Führer and Reich Chancellor.

In a surprisingly short time, Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP managed to liquidate the democratic German republic and establish a totalitarian, racist regime.

An unmistakable sign of the change in regime was the establishment of the first German concentration camps. In March 1933, only two months after the Nazis took power, the concentration camp at Dachau was set up, followed by further similar facilities. Communists, Jews and all kinds of other real or supposed enemies of the Nazi regime were sent to them for alleged reeducation

.