Before Munich

I was born in Varnsdorf. My father worked for two Italian insurance companies, my mother was a trained seamstress, but she only sewed at home - officially she was a housewife. I had a sister, Liana, who was five years younger.

My father was of Jewish origin, my mother wasn't, but before their wedding she converted to the Jewish faith. Later she was persecuted for casting a slur on her race, and she paid for it with her life. In Varnsdorf we lived on the main road, where everything took place.

Margit's parents' wedding photograph - Marie Schmidtová and Alfred Schück. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

I went to a German elementary school. As far as I know, there wasn't even a Czech school in Varnsdorf. But from the second grade onwards we had Czech as an optional subject. Unfortunately we only had it until 1938, after that, of course, there was no more Czech teaching. My sister went to elementary school and that was where her education ended, because then she wasn't allowed to go to any school. I managed to take the entrance exams for grammar school when I was in the fourth grade, and did very well, but I was no longer accepted for racial reasons. I finished elementary school in the fifth grade and went on to an ordinary secondary school, where I went straight into the second grade. That meant that I managed another three grades of secondary school.

After Munich

As soon as the Czech border area became part of the Reich in 1938 I started to come across antisemitism at school, and it was extremely traumatic for me, because until then I had never really been aware of my Jewishness. I know that on certain occasions my father had to wear a hat, but I don't remember Jewish holidays being celebrated in any particular way. Only Long Day, as my father called it, the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, was observed. My mother learnt to cook a great many good Jewish dishes, which I liked very much. I was different from the other children in that I had time off when they had religious education lessons. I also remember that one of our neighbours sometimes used to tell me off for using a Jewish word here or there, she said literally: Du jüdelst schon wieder. I had no idea what she meant by that, and when I asked about it at home, my parents told me: Take no notice of her.

My shock was thus all the greater when I came across open antisemitism in school. I remember it vividly. I came to school on the first day, and I stopped in the doorway, because there were some newspaper cuttings hanging from the blackboard, and the girls were standing around them and shouting and laughing, and when I went into the classroom they took them down and looked at me in a strange way, and I immediately felt that I was part of some sort of game. That's how it started. Every day after that I had antisemitic writing or drawings on my desk. Whenever a guilty party was being sought in the class, the children always said it was me. Some girls even thought up various slanderous things about me, and some teachers punished me unjustly. In a short time I went from being one of the best pupils to being a publicly-vilified victim. The teachers mostly reacted with indifference, although they knew perfectly well that it wasn't true, and some of them relished punishing me. I used to enjoy going to school, but now my relationship with it changed radically. Every morning I shook with fear, wondering what awaited me in the classroom. At home I was afraid to talk about it - my father was already in a camp, and I didn't want to add to my mother's worries when she was up to her ears in difficulties as it was.

There was one girl in particular who stood out as having a rather leader-type personality, and captivated the others. She banned the girls from being friends with me. No one talked to me, and I was suddenly the outcast of the class. It was so bad that at home I cried and refused to carry on going to school. At that point my mother girded herself and we went to see the mother of the class ringleader. I have to say that after that, things were much better. I suddenly found myself under the girl's protection, and from then until the end of the school year things weren't so bad. In the new year, too, the situation was better. The children got used to it, although the bullying from some children and teachers continued. I was not allowed to recite in public, for example, even though I was the best at reciting in the whole school. Or the gym teacher would give me nothing but bad marks, although I did my exercises well.

Kristallnacht in Varnsdorf

The events of Kristallnacht in Varnsdorf are engraved on my memory. That evening we had a visit from a young girl for whom my mother was making a dress for dance classes. They sent me and my sister to bed. Our bedroom looked on to the street, and we were woken up by terrible shouting in the street: Jews out! Jews to the gallows! We both woke up, started crying with fear and ran to find our mother. The girl was still sitting there, and we shouted that we weren't staying there . My mother hugged us and started to cry herself. My grandmother was there too, and she calmed us down, and I remember vividly how the young girl - she was German - went outside and shouted at the mob: Shame on you! Aren't you ashamed, frightening this woman and her children to death? What have they ever done? Shortly afterwards the crowd moved on, but we learnt that the same shouting had taken place outside every house where they had arrested someone that day.

There was a strange atmosphere in general that day. Two policemen came for my father, one was local, still in a Czech uniform, and the other in a German Reich uniform. My father wasn't at home, just my mother and we two children, and my grandmother. My sister and I were playing in the corner with our toys. The German Reich policeman said, somewhat awkwardly: There are children playing here. But the local one - he even used to go to school with my father - was far more impenetrable. Then they left and waited in front of the house until my father returned. When they came upstairs with him, my father was joking, he asked if he had time for coffee. They said there wasn't time, and my mother started to cry. My father comforted her and said: Look, what are you worrying about, I haven't done anything to anyone, I'm not afraid of anything, there's been some mistake and it will all be explained soon. That was the first great earthquake, and it engraved itself on my childish psyche and has never disappeared. Many times I have thought that the passing of the years has healed it, that it's gone, but then I find that it's still incredibly vivid, that today it seems to hurt even more than before.

They took my father to Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen. For a long time we didn't know. My mother found out from people she knew, the wives of Jewish men who had also been arrested, that they spent the first night in the cells in Varnsdorf, they called it Schutzhaft, protective custody. Then they took them somewhere, no one knew where, and it took a long time - I no longer know how long, but it seemed endless to us - before the first letter came, written in printed letters, from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In the prescribed thirty words he wrote that he was doing well, and that he hoped we children were being good, just a neutral letter.

He came home at Christmas, but he was in an awful state. His hands and feet were frostbitten to the bone. We called the doctor, who treated him, and my mother wanted to know more details, but all my father said was: Don't ask me, I've had to swear that I won't say anything to anyone. And he really didn't tell us anything. I don't know if he told my mother anything when they were alone, but whenever we children were there, he never said a word. As soon as his hands and feet had healed and he was capable of normal life, once he could walk and pick things up, he went to Prague, and stayed there until the transport to Terezín.

Life without my father

It is interesting that, long before that, there had been talks and discussions in my family about the possibility of emigrating

to England. I remember that in a room in the attic we had big boxes packed with some precious china that was to be moved.

But it was only ever discussed, nothing ever actually happened. Shortly before the occupation, my mother wrote to my father,

begging him to leave for London and not to stay in Prague, because the Germans would definitely come to Prague too. I still

have my father's answer, in which he writes: Don't be silly, Germans in Prague, that just wouldn't happen. My mother turned

out to be right, and it became reality faster than anyone thought it would. At the time of the Munich agreement my parents

decided that we should at least go to Prague. They had a friend who was a taxi driver, who sometimes took us on trips on Sundays,

and he said it was no longer possible, because there was shooting at the Šébr pass. I remember the mobilisation period,

above all my brave grandmother. It started with the Turner gymnasts and other men marching past, shouting Women and children

to the border!

And that everyone would be evacuated to the Reich. Of course we didn't go anywhere, but most of the Germans

went. Our town, which at that time had a population of 23,000, was completely deserted. When the Czech unit came, it was a

huge relief. Unfortunately that lasted only a short time. I remember my grandmother going shopping and coming back full of

joy; she told us she'd been talking with Czech soldiers who had given her a hand grenade to feel. It looked like an egg, apparently.

My grandmother said: They won't hand us over, don't worry! She was full of optimism. But then the Czech borderlands were ceded,

and the Germans came.

We were alone in Varnsdorf. My father was living in Prague at various addresses, we had a very large family and a huge number of various aunts and uncles. We went to visit some with my mother when we arrived in Prague. My father was waiting for us at the station, we threw ourselves at him and shouted with joy at seeing him. The first thing he told us was that we had to whisper, that people didn't speak German here. He was embarrassed that we didn't really know Czech.

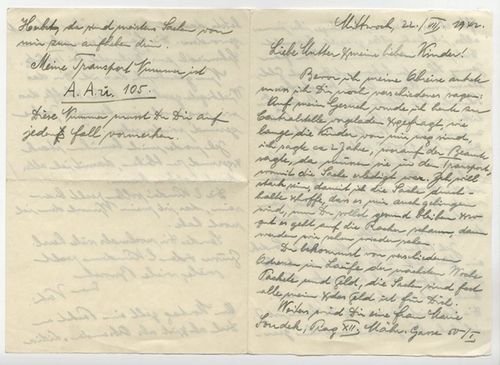

Part of Margit's father's letter to her grandmother in Varnsdorf before the transport to Terezín. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

My father earned his living in Prague in any way he could, including gardening in the Old Jewish Cemetery, sweeping the road, clearing snow and whatever he could do to earn a living in some way. He spent a relatively long time in Prague, he was deported to Terezín on transport AAu, in which he had the number 105. I remember the number precisely. I think it was in 1942. The post from Terezín came regularly once a month, a note similar to that which we had from Sachsenhausen, and we could even send parcels there. I remember that my sister was friends with a girl whose father was a butcher. He sometimes gave us a bit of salami. My grandmother, who insisted that everything must be sent to Terezín, used to bake cakes, rather strange ones out of potatoes and a bit of flour to keep it together, and sent them to my father - who, by the way, had once been very picky about his food. Now, with enormous gratitude he thanked us for the very small packages that we were able to send him, and which he was clearly receiving. Then the letters stopped, nothing came, and my grandmother was afraid he was no longer there, but I didn't want to admit it. By that time we already knew that the war was coming to an end.

Letter from Margit's father in Terezín in which he thanks them for the parcels sent, and praises their contents. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

My mother tried to earn money by sewing, and she had a few acquaintances who asked her to make clothes. She must have earned something, because I can't imagine that we would have lived off my grandmother's pension alone. I remember that my mother was increasingly losing her mental stability, she didn't know what to do, and she would succumb to utter gloom. The Germans urged her to divorce - that, they said, would make everything easier, and above all would save the children. It was a very hard decision for my mother. It looked at one point as if she would succumb to the pressure. She went off to Česká Lípa, I think there was a Landrat or an Oberlandrat there, where it seems they gave her instructions as to how to proceed. Then she insisted that she had to go and see my father in Prague so that she could discuss it with him, since if she did agree to it, it would of course only be a fake divorce, not a real one. That made me realise that she loved my father deeply. She really did manage to get to Prague and to agree with my father that they would divorce. In the end, however, my mother refused to get divorced. In that one matter she was very strong.

So the situation stayed the same, and she was tormented and bullied more and more. Numerous times my mother came home in tears, and, frightened to death, recounted various incidents - that someone had crossed over to the other side of the road, that someone had said something nasty to her face. In short, it was daily bullying, which clearly she could no longer take. After a while, only my grandmother did the shopping, since she was not afraid and knew just what to say to everyone, whereas my mother was depressed and would start crying immediately. I think that it was this quality in her character that made her such an easy and welcome victim, on which the Nazis unleashed all their passions. She was repeatedly called up in front of the authorities. The Gestapo searched our house several times, slashing the mattresses and damaging the furniture, throwing everything around, and it was very, very bad. For my mother these were traumatic experiences, which mounted up in her head and gradually led to pathological hysteria.

One day my mother received a summons to go to some office or other where they clearly threatened to imprison her, maybe even send her to a camp, but above all to take her children away. At that point she succumbed to utter despair, and became obsessed with the idea that she had to protect her children. And protecting her children meant to her that she had to put herself out of the way. The Germans also emphasised that she was responsible for her own and our fates, that if she had got divorced, the whole affair would have been sorted and she would have had been left in peace. She had a few pieces of jewellery, not much, but she was clearly very attached to them, maybe her father had given them to her. One day she went off and took the things to a friend, saying that they would be safe there, and that if the Gestapo came to our house again, they would take them from us anyway, just as we had earlier had to hand over our radio. Later she was always saying that she should have brought the jewellery back again, but that she never found the courage to do so.

At Easter 1940 she decided to take her own life. I used to sleep with her in the double bed, while my sister slept in a children's bed. I was woken up by a noise. My mother was in the window. I couldn't tell what she was doing, because I've been very short sighted since birth, and without my glasses I wasn't able to tell. I called to her: What are you doing, Mummy? but she did not answer. Suddenly there was silence, but I had the feeling that something terrible had happened. I shouted out, and ran to get my grandmother. Together we cut her down and brought her back to life. My mother was angry with us for doing it. She had an ugly red mark on her neck, but soon she recovered. She lamented: Why didn't you leave me? Everything would have been sorted out.

I was just over ten years old, and as a result of all these events and the whole way in which things had developed, I rapidly lost my childhood, my childish way of thinking about things, my childish ideas. My mother was always talking to me as a partner, and wanted me to comfort her, and I tried terribly hard to comfort and help her. But at the same time I was afraid of all those outpourings, the hysterical shouting and crying that always accompanied it. It frightened me, and, to be honest, I tried to avoid it, and would go outside or read, I felt that I couldn't bear it alone. Nevertheless, I still blame myself for not having done more for her.

After her suicide attempt I made my mother promise that she would never do it again, but my mother said: I can't promise you,

but I will promise that I won't do it before I've brought the jewellery back for you. Since in the past she had talked long

and often about the fact that she would have to bring it back, but she never did, I satisfied myself with that. And then one

day, I remember it as if it were today, I was sitting on the sofa in the living room, reading a book. My mother came in and

said in a largely cheerful voice: I've brought the jewellery. And I just raised my head a little and said Yes?

and she said

Yes

. And I carried on reading. My mother sat down and unwrapped her treasure. There were pearls there, a string of pearls

that her father had clearly given her for her wedding. It was a hot day and the windows were open, and suddenly my mother

hurled the pearls out of the window. The river Mandava flowed under the windows, and the pearls drowned in it. My mother said:

Pearls mean tears, and I hardly have any left. I was startled by what she had done, but I had the feeling that it had brought

her relief. I just blame myself for the fact that I paid no attention to the actual fact that my mother had brought the jewellery

home.

The next day, as I was coming home from school, I saw my grandmother standing in front of the house. I am so short sighted that I cannot recognise anyone at any great distance, but that time I recognised my grandmother precisely, even though she was still a long way off. And I knew what had happened even before I reached her. And I wasn't wrong. My mother died almost a month after her first suicide attempt, in April 1940, I remember that her funeral was on Hitler's birthday, 20 April.

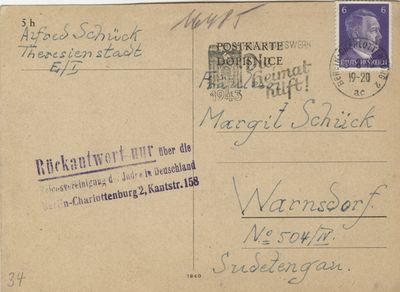

Postcard from Margit's father in Prague, in which he asks her to find flowers for her mother's grave. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

They didn't allow my father to come to my mother's funeral, but later they did allow him to visit Varnsdorf so that he could deal with my mother's estate. What it consisted of I can't say, because we really didn't have any property to speak of, but maybe he had to sign something to say that everything belonged to the children, I don't know. He was only with us for a very short time, his permit was for about two days. Our neighbour immediately went to tell the Gestapo that Mr. Schück was here, and that if that stinking Jew stayed here, she wouldn't live with him under one roof. My father returned to Prague, and we wrote to each other regularly, I was in charge of the correspondence, my grandmother usually added a few words and my sister was only just learning to write. I still have all the letters, although I have cut off all the stamps with Hitler's portrait.

Life without my mother

After my mother's death, my grandmother took care of us. She took over responsibility for bringing us up, although the Germans offered to take us into an orphanage. My grandmother wouldn't have it, although she was sixty-seven at the time. My grandmother was very small, but spare, with a huge amount of understanding for us children, and great inner strength. She managed to deal with everything, she had never-ending optimism, and she knew how to fight. I remember that when the Soviet Union was attacked, our fanatical neighbours once again caused a rumpus and told us that it was all the fault of the Jews. Our grandmother wasted no time in going to tell them off for saying such stupid things to children. In short, my grandmother was afraid of no one and nothing, and found the courage to do anything if she considered it necessary. I think my sister and I have my grandmother to thank for the fact that we even survived. At that time, after leaving secondary school, German girls had to work in a family, it was called a Pflichtjahr, and so when I finished school, the labour office assigned me to a family that, by chance, moved from Varnsdorf to Vrchlabí soon afterwards. They told me I could come with them if I wanted, so I did. I was with them for nine months, and was essentially their maid. The wife was a committed national socialist, but she didn't behave towards me as badly as you might have thought. Her husband was a soldier. They had two daughters, the younger of whom was the same age as my sister. She was a terribly malicious little creature, constantly bulling, provoking and needling me in this sort of way: Mummy says you have to put up with everything because you're a Jew. I was awfully angry with the girl, but I have to say that by that time I had learnt how to control myself well. I said nothing out loud, I didn't apologise, I just thought my own thoughts, but I was choking with helpless anger. I knew that as soon as I opened my mouth I would get such a slap that I would remember it for ever, or that it would cost me my life.

Margit's grandparents' wedding photograph - Antonie Zemanová and Anton Schmidt. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

In exchange for this service, I had accommodation, food and pocket money - eight marks a month. This is also interesting: at that time there were food coupons, and although my sister and I were young people or children, we had food coupons for outcasts - with no meat, no butter, just bread, potatoes, a little sugar, pasta and I don't know what else. Only my grandmother had normal coupons, because she was an Aryan, she was a Czech who married a German.

I stayed in that family for nine months, and then they called me into the labour office and told me that the Pflichtjahr was honorary service to the German nation, but that I was not worthy of it and that I had to leave the family immediately and go and work for a farmer. According to the Labour Office's decision, I was supposed to start working for a farmer in the Krkonoše. I went to see them, and it was terrible. A house by itself on a hill, everyone lived in one room, family, children, animals. It was incredibly rank and dirty, awful conditions. When I told the labour office that they didn't have anywhere for me to sleep, they replied with a malevolent smile: There's room everywhere for your sort. I was in despair, I wrote and told my grandmother what had happened, and once again my grandmother got to work. In a very short time I received a letter from her telling me not to wait, but to pack my things and come home because she'd found me work at a farmer's in Varnsdorf.

And so I came home. I worked for the farmer for a short time, but they sound found out that I was utterly unsuited to that type of work, since during the month I was there I managed to break my glasses while chopping wood, injure myself with a fork while spreading manure, and break my hand falling off a hay cart. Soon they didn't want me any more, because I was forever sick and forever spoiling things. In addition, I made use of every free minute to read. Since my only free minutes were when I was on the loo, the farmers soon found out.

Then I started work for a gardener in Varnsdorf, where I did everything that needed doing, and it was a very pleasant time - unfortunately also a short one which only lasted until autumn, since after that the gardener had no work. The gardener used to go to school with my father, and politically he was very much against the Hitler regime, so we got on very well. He even gave me a few of the vegetables we grew, to help out our poor household.

When I finished working for the gardener, the labour office sent me to work in a munitions factory as forced labour. It should be mentioned, however, that the Plauert factory in Varnsdorf was known as a bastion of social democrats and communists, and that is where I learnt what solidarity is, in the best sense of the word. First of all I was put on the grinding machine, where before long I ground my finger, and so they moved me to the drill, where I also had a minor injury. There were always long and complicated investigations as to whether it was sabotage. Finally, I worked in the tool room. I had only been there for a very short time when a man came up to me and said he knew my story, my parents and above all my father, and asked if we were in contact with him - my father was in Terezín at the time. Then he started bringing me food for him, and cigarettes, usually only two or three at a time, because they were very valuable items. In addition, he let me know who I should and shouldn't talk to, and where I should be careful of what I said. However, I was a young loudmouth - I was fourteen - and sometimes I behaved in ways that make me amazed today that I got away with it. For example, I went to see a worker whom I had been told was a reliable person, and I said to him: Mr. Tischler, you're not in the party, are you? He looked at me and said: What are you talking about? And I said: I know you were in a party that isn't allowed to exist any more. Of course he told me to get lost, and he was absolutely right. Although they kept trying to move me in the factory to the worst type of work, like washing windows and dragging heavy pieces of steel, there were always people who would step in at a certain moment by saying, for example, that that was enough and that I had to do something else. I stayed in the factory until just before the end of the war.

Liberation

I don't know exactly on what day it finished in Varnsdorf, when the Soviet Army came, whether it was May 7th, 8th or 9th, but I remember it very well. As usual, my sister and I were in front of the house - we spent a large amount of time there - and we looked on and welcomed the army, waving and shouting - we were happy. But the soldiers and civilians looked at us as if we were mad. Of course the Germans had all retreated inside, they had the windows boarded up or they were peeking out from behind the curtains, and we could feel directly their hostile looks at our backs. But we were no longer afraid of anything, and above all we were looking forward to our father coming home soon.

It might be interesting if I said something about the evacuation of the Germans as I experienced it, since it's a much-discussed issue today. Above all it seemed to me to be entirely just. When the Germans complained that it was unjust, I replied to them at the time: Our people went to their deaths, you are only going to another life, so you have no right to complain. Of course that derived from my personal experiences, I saw it through the lense of the tragedy of our whole family, and clearly there was also a certain element of revenge or just deserts. Nevertheless, we distinguished between Germans. There was a family living in our building that had moved her during the war, they had been bombed out and they were given a flat in our building that was free. They were a young woman, her invalid husband and a little child. The Czechs came to arrest the man, and his wife ran crying to my grandmother. All the time they had lived in our building they had been very polite to us, they had been uncommonly respectful to my grandmother and helped her whenever they could. So my fearless grandmother went to defend him. In front of her eyes they pulled off his shirt, so they could see he had an SS number tattooed under his arm, and after that there was nothing she could do. The wife had to go to a collection camp, and we let their little boy stay with us until they were transported to Germany.

Another family had a different fate - a family with whom I am still in contact, or rather with the daughter, since her parents are no longer alive. As a schoolgirl I used to go and play with them, and look after the little girl. I was about twelve or a little bit younger, and the little girl was five. Her parents had a lot of work, and they needed someone to look after their daughter. I said that I would, I wanted to lighten the burden on my grandmother a little, because she received nine marks a month for each of us. She herself had, I think, a pension of twenty-seven marks, and on that she had to get by, and so she did. The Jakubetz family were very good and kind to me, and in 1945, when they were to be removed from the country, I felt it was my duty to help them. I went to the Soviet command, where I insisted on seeing the commander - all in German, because I didn't speak Czech, and definitely not Russian. I didn't take them a white strip like the Germans, I didn't feel I was a German, although I only spoke German. I don't know who it was that I spoke to in the end, but I just told them about those people and I really did get an exemption for them, and they were taken out of the transfer. Unfortunately only out of the first one, since when further ones followed, the Czech official in charge tore up the piece of paper and they were transferred all the same. It is interesting that they were never bitter towards Czechoslovakia; on the contrary, they have a very warm relationship towards it.

I don't know about any excesses during which Germans were actually harmed, I didn't see anything of that sort, I think that where we lived it took place in an orderly manner, although in the tense revolutionary atmosphere of the time, because during the period after the war, national emotions necessarily ran high, and there were all sorts of passions. Certainly, the Germans were not handled with kid gloves, but I didn't see or even hear of anyone being tortured or beaten, and I think I would have heard if there had been, since very many people we knew were removed. I have one more particularly vivid memory of the Soviet soldiers. There was a hairdresser's in our building, which was naturally closed during that turbulent time. A Soviet jeep drove up, and some women in military uniform got out of it and insisted on seeing the hairdresser. I went to find the hairdresser, who was immediately terribly frightened and, in a state of great alarm, went to comb and curl the Russian ladies' hair. The driver remained seated outside, and my sister and I went to try and talk to him, which was fairly difficult. Nevertheless, we somehow managed to, and in the end we invited him in to our flat. My grandmother had more luck talking to him in Czech, and she told him our family's story. When the women had had their hair curled, they told me I could go with them if I wanted. They drove to the nearest bakery, where one of the women soldiers ordered bread. When the German baker asked for coupons, she said she had none, and she pulled out some money, it was some strange kind of Allied money. The baker hesitated to accept it, but she of course knew how to make her wishes felt. She took two large loaves of bread, and we went back to the jeep. They took me to the military command, where I was also given jam, some socks, artificial honey and the two loaves of bread. Then they put me back in the jeep and took me home. This incident was interpreted very badly, and when shortly afterwards I went to see my aunt, where we used to listen to the radio, she had already been told that I had been out looting the shops with Soviet soldiers.

We waited impatiently for my father, but he still hadn't come back. Most of my friends had moved away from Varnsdorf or been transferred, and so I felt quite lonely. I started to think about what would happen next. My first task was to learn Czech fast. I tried as hard as I could - with the help of my grandmother, who spoke only Czech to Liana and me. In order to become perfect I needed to live in a genuinely Czech environment, and I was also very keen to get into some sort of school. I considered it highly unfair that I hadn't been able to go to secondary school and been able to study, because I loved school. In addition, I longed to go to Prague. The mere name enchanted me, it was exciting and full of promise. Moreover, it was the place to which my father had gone when he returned from the camp, it had given him temporary refuge and he himself saw hope in it.

Margit Maršálková in Mariánské Lázně, 1946. (Photo: archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague)

Then a letter came from Mrs. Ranschburgrová, who had known my father in Terezín and had found us in Varnsdorf. They had promised each other that whoever survived would look after the children Mrs. Ranschburgrová had survived with her very invalid husband and her daughter. They had also killed her son. From her letter we learned that my father had been in Terezín until October 1944, when he was sent on one of the last transports to the gas chambers in Auschwitz. She invited me to Prague, where we went round all the possible institutions and offices, to try and gain orphans' pensions for me and my sister and some sort of help from JOINT. Her family provided a base for me in Prague, although I stayed in Varnsdorf for some time after that. We still wrote to each other, and one day I just decided that I had to go to Prague. I went, and told Mrs. Ranschburgerová. She thought I was completely mad, because I couldn't live in Prague when I didn't know the language.

My grandmother had relatives in Prague too, though, and they helped me. They were called Zeman, like my grandmother when she was single, and they had a salon at the bottom of Wenceslas Square, next to Baťa on the first floor, where they made bras and corsets. They lived in Žitná street. One of their employees was just getting divorced, and she was looking for someone to look after her five-year-old son. At that moment I appeared on the scene, and jumped at the opportunity. I also went to Czech courses, and tried to read Czech books, although I didn't understand them very well.

After that, events started to unfold normally, I met more and more people, who helped me to sit the external school-leaving exam at the British Institute, I got into university and thus fulfilled my dream. None of my father's many Prague relatives had come home. His mother, who lived with her daughter in Vienna, had died before the transport. We never heard anything more about my father's sister. My father's brother and his eldest son also died in Auschwitz. His widow returned with their daughter Eva and younger son Viki, who left shortly after that and lived in Israel until his death.