European anti-Semites of all shades had traditionally called for the exclusion of Jews from the national community, their isolation and the limitation of their rights (see, for example, Rudolf Vrba's National Self-Defence programmeof 1897; in Czech). Essentially, these were calls for the renewal of the medieval ghettos, but in this case ghettos without walls, with borders that were not territorial, but consisted of inflicting bans and limitations on Jews. Jews would become second-class citizens, against whom the majority of society allegedly had to defend itself, and who could be at the very best tolerated on the territory of this or that nation. The Nazis began to implement these ideas within the Protectorate. Countless decrees and edicts issued by the Protectorate authorities were designed to isolate Jews from the rest of society.

Jews were banned from entering certain streets, squares, parks, woods and other public places. From September 1939 on, they were not allowed to stay outside their houses after eight o'clock in the evening. From November 1940 on, Jews were not allowed to leave their municipalities, even temporarily, without special permission. Jews were not allowed to visit theatres and cinemas, pubs or cafés, swimming pools, libraries and other sporting and entertainment facilities. When travelling by city public transport, Jews were confined to standing in the last carriage. In trains, they were not allowed to use the dining or sleeping cars, and they were allowed to travel only in the lowest class - and once again, only in the last carriage. They were banned from entering waiting rooms and other railway facilities. Shopping times for Jews were limited to two hours twice a day, later two hours a day. Jews had their radio sets taken away, were limited in their choice of food, and were not allowed to keep pets. Many more such bans and orders could be listed, all of them designed to humiliate Jews and set up an invisible wall between them and the rest of the population.

As part of what was called the Aryanisation of Jewish property, Jews had to declare all their property, including works of art, jewellery, real estate, radios, bank accounts and insurance policies. They were not allowed to deal freely with this property, and it was later confiscated, falling into the hands of the Reich. Jews were driven out of their flats, and several families often had to move in with each other. A government decree of October 1939 allowed Jews to be dismissed from their jobs with no right to compensation or benefits. Jews could be called up for forced labour, had no right to paid holidays, had to be kept separate from other employees and were not covered by health and safety regulations or working hours regulations.

Jewish children were banned from attending German schools, and from August 1940 on, also from Czech public and private schools. From 1941 on, the training courses organised by the Jewish religious community were also banned, and from July 1942 on, teaching in Jewish schools was also no longer allowed. Despite the ban on private teaching, however, secret lessons were organised for Jewish children.

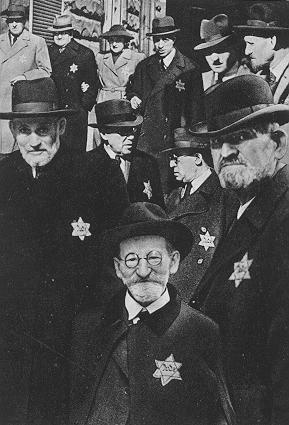

In order to ensure that Jews were kept separate in society, they had to be easily identifiable. From March 1940 on, Jews' identity cards were marked with the letter J

for Jude (Jew). From the 1st of September of 1941 onward, all Jews aged six and above were only allowed to appear in public if they wore a yellow six-pointed star bearing the word Jude

on their clothes. Citizens of the Protectorate were also warned in the press not to show any sympathy towards Jews thus labelled, or they would be dealt with as the Jews were.

Photographs from the publication The Secrets of the Jewish Cemetery in Prague (In Czech) published in 1942 as part of the Nazis' anti-Semitic campaign.

Displays of anti-Semitism and the persecution of Jews became part of the everyday life of inhabitants of the Protectorate. On the other hand, the common enemy - Nazi Germany - and simple human compassion helped to blunt Czech anti-Semitism. Many Czechs helped their Jewish friends and neighbours to overcome the all-encompassing bans and decrees, and helped those who were hiding from the deportations to survive in hiding. However, most people behaved impassively in the face of the persecution of Jews, not wanting to expose themselves or their families to danger.

-

Literature:

-

Petrův, Helena. Židé v legislativě Protektorátu Čechy a Morava (Juden in der Gesetzgebung des Protektorats Böhmen und Mähren). Praha: Institut Terezínské iniciativy - Sefer, 2000.

-

Lagus, Karel, Polák, Josef and Polák, Karel. Město za mřížemi (Stadt hinter Gittern). Praha: Naše vojsko - SPB, 1964. 365 p.