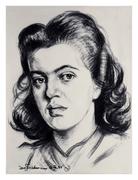

Between 1939 and 1941, I drew and painted almost everything in Prague, especially many portraits of prominent Jews and personalities,

such as the president of all the Jewish Congregations in Czechoslovakia, [František] Weidmann, the vice-president Jakob Edelstein,

and many others. I also drew many portraits of officials from the Palestine Office. Some of these photo reproductions came

into my possession once again in 1946. However, every artwork that was produced until 1938 in Germany, and later in Prague

until 1941 was lost.

1

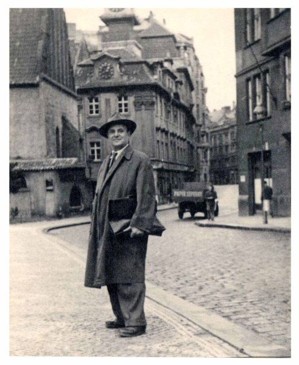

Author's archive: David Friedmann, Prague 1948.

David Friedman(n) was born in 1893 in Mährisch Ostrau, Austria-Hungary, today Ostrava, Czechia. Since childhood, I watched

my father paint with intensity and passion. I was intrigued about his prewar life and the fate of his Nazi-looted art in Berlin

and in Prague. My father had little to show from a collection that had numbered 2,000 paintings, drawings, etchings and lithographs.

The German Reich had eradicated nearly every trace of him. Miraculously, an album survived the Nazi destruction. Quietly my

father watched me view his Berlin works and the captivating 1940 to 1941 portraits of the Prague Jewish Community. Displayed

on the following pages were postwar art depicting his experiences during the Holocaust and after liberation.

At my request, my father entrusted this treasure to me despite my age of 22 years. I understood the portraits were evidence of a dynamic Jewish community that had been destroyed. I felt a sense of satisfaction that at least some of his work had survived. Already my thoughts were that I must rescue David Friedmann and his legacy from oblivion. However, I was still at the beginning of my journey and there was yet an unfathomable history to learn, discoveries to find and piece together over the course of more than four decades.

David Friedmann was seventeen years old when he ventured to Berlin and studied etching with Hermann Struck and painting with

Lovis Corinth. He achieved acclaim as a painter known for his portraits drawn from life and became a leading press artist

of the 1920’s. He produced hundreds of portraits of famous contemporary personalities, such as Albert Einstein, Max Brod,

Richard Réti, Jan Kubelík and Arnold Schoenberg. My father’s talent for portraiture played a central role throughout his

career and saved his life during the Holocaust.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, David Friedmann’s successful prewar career abruptly ended. In December 1938, he fled

Nazi Germany with his wife Mathilde and infant daughter Mirjam Helene, with only his artistic talent as a means to survive. He

writes in his 1973 testimony, Das Krafft Quartett

:

From the time of my escape from Berlin to Prague, I was trying to get acquainted with the members of its Jewish Community

to call their attention to my ability as a portraitist. Once I made it known that I had the intention of putting together

an album of portraits, the orders came in abundance.

On October, 16, 1941, the Friedmann family was deported on the first transport from Prague to the Łódź Ghetto in occupied

Poland. When the ghetto was liquidated at the end of August 1944, he was separated from his wife and child never to see them

again. He survived Auschwitz and other concentration camps, and returned to Prague. The responsibility to bear witness weighed

heavily on his consciousness even before his deportation. Torn from his memories he created the powerful series, Because

They Were Jews!

The art shows the evolution of the Holocaust from his deportation to the Łódź Ghetto through to liberation

in 1945 and conveys the ever-present terror, mercilessness, brutality, and death that innocent men, women, and children suffered

during the Nazi regime. His postwar journey led from Czechoslovakia via Israel to St. Louis, Missouri, where he continued

to paint until his death in 1980.

After my father died, I grasped the enormity of his gift and the responsibility that came with it. I wondered how my father

could part with this historically significant album, a profound piece of his past and the people he sketched and befriended.

The expressions my father chose, the attitude of his line, even the shading, all show us his thoughts together with his handwritten

commentary. The mood was somber; the faces reflect the stress of persecution and an uncertain future. The majority of subjects

were sent to Theresienstadt and murdered in Auschwitz.

Each portrait tells a story. I knew the likes of Edelstein, Zelenka and Hirsch. The challenge was to identify the unknowns—those

with illegible signatures or none at all. Incredibly I found the correct match for common surnames, such as Stein, Klein and

Bergmann. However, a complete name does not guarantee success, for example, the portraits of Hans Kaminsky, Otto Löwy and

Fritz Löwenstein.

Ten pieces, portraits and landscapes, surfaced in the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague. Eight of these works, including

two portrait drawings, were Nazi-looted art. A third portrait drawing was donated to the Museum. Thus, my father’s method

of working came to light. He used the large-sized portraits to produce the smaller reproductions. Portrait prints, some identical,

surfaced at the National Museum in Prague, Beit Theresienstadt in Givat Haim Ihud, Israel, and in two family-owned collections.

The discoveries confirmed the portraits were ordered in multiples and exchanged between colleagues and friends, often with

dedications written on the reverse side.

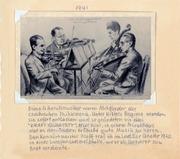

My father’s love for music carried through in his art even during the worst of times. Among the pages of his album I was

struck by a drawing of four musicians entitled, Das Krafft Quartett.

The Nazi regime aimed to deny all Jews their rights and

even the solace that music provides. The Jews would gather to enjoy clandestine performances of musicians just to experience

a few hours away from grim reality. The drawing is the only document to survive of this quartet. Besides commenting in the

album, my father wrote another testimony, a fitting introduction to the portraits and his own story.

From the first time I saw my father’s album I was overwhelmed with the need to share his work and find the connections

to his past. One of the starkest traumas of the Holocaust—people not only lost their lives, but also traces of their existence.

A portrait may be the only image to remain of the victim. Perhaps an unknown subject can still be identified, a lost artwork

found. I donated the Album of David Friedmann

to Yad Vashem Art Museum in Jerusalem. Thanks to the collaboration with the

Terezin Initiative Institute, the Jewish Museum in Prague, Yad Vashem, Beit Theresienstadt, the Chudy and Kraus families,

the surviving portraits of the Prague Jewish Community appear online as a shared mission of education and remembrance. The

fates of the known subjects are synchronized with the database of victims—Holocaust.cz. This has been the most rewarding

aspect of my journey, to have David Friedmann’s work recognized as a valuable resource—an important contribution to Holocaust

history and the art world. His portraits are preserved for future generations.

August 28, 2018