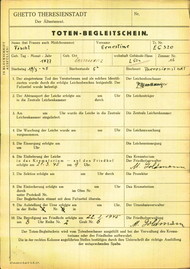

The burning synagogue in Most, 10 November 1938

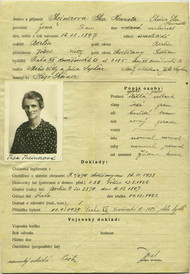

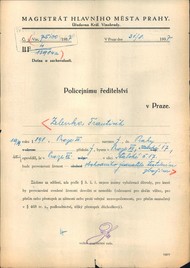

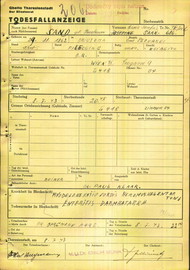

There is relatively little awareness in the historical subconsciousness of the Czech public that „Kristallnacht“ also took place in the border regions of the Czech Republic, the area that had become part of Germany under the Munich Agreement of 30 September 1938. The course of Kristallnacht in this area was influenced by the fact that it took place only a few weeks after occupation, in towns studded by swastikas, at a period when Jewish property was being „Aryanised“ at a rapid rate. Kristallnacht in the border regions thus took place against a background of the passions, enthusiasm and terror roused by the Munich verdict. Many Sudeten Germans were hurrying to join the Nazi Party or the newly-created SA units, and longed for „revenge“ against Jews and Czechs. Even before 9 November, formerly-significant Jewish communities in the border regions were already being torn apart: of the approximately 28,000 Jews who had lived in the area before the Munich agreement, at least 12,000 had left. Jews and the Nazis' political opponents had already fled from the border area out of justified fear of violence from Nazi units, especially during the May mobilisation and when the conflict stepped up in September. By November, the synagogues in many places were already closed, and the Jewish communities there were no longer functioning. The Jewish families who stayed were largely those who had non-Jewish relatives. Despite the barriers put in the way of Jewish refugees by the Czechoslovak authorities, most Sudeten Jews managed to reach the Bohemian interior. However, most of them were later deported from there to ghettos and concentration camps.

It is striking how difficult it is in many cases to piece together what happened during Kristallnacht in the border areas. There are still places today where all that is known is that between the Munich agreement and 1945 the synagogue was destroyed or damaged, and the graveyard vandalised or laid waste. Official documents are in many places extremely scanty, and the period press, which served as organised propaganda, was full of antisemitic articles portraying the Paris assassination as an expression of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. Above all, however, there is a lack of eyewitness testimonies: the interviews with Jewish eyewitnesses that have been and are being filmed by the Jewish Museum in Prague can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Even if we add the published accounts, the pogrom in the border area has left little trace in the collective memory. In the memory of Sudeten Germans, the anti-Jewish violence after the Munich agreement plays a minimal role - and thus there is an absolute minimum of memories among Czech Germans of the burning synagogues and the arrests.

Who were the perpetrators?

The passing of time and lack of sources make it difficult to judge exactly who the perpetrators were. The Sudeten German postwar tradition often says that the Nazis were not yet so firmly established in the border regions, so soon after the Munich agreement, and that local people hesitated to take place in an organised anti-Jewish pogrom. However, it is clear that - as in the „Old Reich“, the main actors were the local SA units, the Hitlerjugend and, to a certain extent, also the auxiliary police, SS members or Gestapo. Members of the original organisations of Heinlein's Sudeten German Party had become part of these organisations. It was they who, whether members of the paramilitary Sudetendeutscher Freicorps or youth organisations, were in large part behind the violence against Czechs, Jews and the political opponents of Nazism, both before and after the Munich agreement. Indeed, it would have been very surprising had these radicalised units, prepared for violence, not taken part in the anti-Jewish violence.

On the other hand, however, the burning of the synagogues and other violent acts were far from being a spontaneous display of public anger, as Nazi propaganda would have it. While the perfomance of these activities remained in the hands of a small group of - usually organised - Nazis, most Sudeten Germans merely watched the synagogues being set on fire and the arrests. They did show a great amount of interest: reports from several places state that the synagogue fires attracted the attention of local inhabitants - but whether they were shocked, indifferent or approved of the violence is hard to tell. Criticism of the unnecessary destruction of property appears to have been common. However, attempts to help the persecuted Jews were rare: whether out of fear, or out of agreement with the Nazis. If Sudeten Germans did try to save the synagogues, something of which there is evidence in several places, they were not openly expressing rejection of Nazism or antisemitism, but were afraid of the danger to surrounding buildings. Sometimes they organised the activity in a purely formal way, so that the building was not destroyed. The town councillors in Krnov, for example, seem to have cunningly got round the order by setting fire only to the ceremony room in the cemetery, and not to the synagogue itself: they declared that the „temple“ was the town marketplace.

In total, according to research so far, approximately 35 synagogues in the border regions were burned down or otherwise damaged, and an unknown number of Jewish men were sent to the concentration camps at Dachau and Sachsenhausen. Those who survived were forced to sign an undertaking to emigrate from German territory as rapidly as possible. Further Jews were imprisoned in improvised camps set up in over ten places in the Sudetenland. The violence and expulsions reduced the Jewish community in the border areas to a mere fragment of what it had been.

The seventieth anniversary of the November pogrom in the border lands is not only significant because of last year's attempt by Czech neo-Nazis to march through the Josefov district of Prague, but also because we are commemorating the fates of the extinct Jewish communities and their co-existence with the majority society. The fragments of their fates are only gradually being put together by local historians. The history of the co-existence of Jews, Germans and Czechs in the Czech border area thus has yet to be written.