Once the Protectorate was established, the Protectorate government gradually adopted all the “anti-Gypsy” regulations that were implemented in Nazi Germany during the 1930s. At first, however, the new regime used the legal measures and the practical implementation of the persecution of the population described as“ gypsies”, based primarily on the First Czechoslovak Republic‘s law No. 117/27 of 15 July 1927 “On wandering gypsies and people living in a gypsy way”. People who were labeled “gypsies” under this law were, among other things, denied access to certain areas, such as border areas, spas, certain districts of larger cities, etc.1 By decree of the Protectorate Minister of the Interior Josef Ježek of 30 November 1939, all “wandering gypsies” were banned from travelling by the end of January, 1940 and were ordered to settle either in their home village, that is the village where they legally posessed a right of residence2, or in the place they were currently staying. The settlement itself did not proceed smoothly, as municipalities often tried to prevent the settlement of “wandering gypsies” by expelling them from their district or denying them the right of residence. After settlement, people were practically under the constant control of local gendarmes, and the Protectorate administration could use periodic reports from individual offices to clarify their records. A census counted a total of 6,540 “gypsies” in the Protectorate on April 1, 1940.3

Ill. 1.: A Roma family after forced settlement, 1940.

One of the possible punishments for non-compliance with the travel ban was imprisonment in disciplinary work camps. These camps were opened on August 10, 1940 in Lety u Písku and in Hodonín u Kunštátu. The decree on their establishment was approved by the Czecho-Slovak government of Rudolf Beran on March 2, 1939, thus before the establishment of the Protectorate. The disciplinary work camps served for the internment of “workshy” men, including “wandering gypsies fit for work”. Men older than eighteen years who could not prove their source of livelihood were to be placed in disciplinary labor camps.4 After the ban on nomadism, men from Roma families who would still travel also were seen as “unable to prove their source of livelihood”. Prisoners of the disciplinary labor camps considered “gypsies” were identified in the camp records by a capital letter “C” (ie, “cikán” or “gypsy”). Depending on the season, they usually made up 5 to 25 % of all internees.5

An important step in the development of Nazi persecution in the Protectorate was Regulation No. 89/42 Sb. on the “preventive fight against crime”, which was a copy of the German decree of the same name issued by the German chief of SS and Heinrich Himmler in 1937. The Protectorate government chaired by Jaroslav Krejčí adopted the decree and issued it on March 9, 1942. Among other things, the criminal police were given the right to impose indefinite detention in newly established detention camps on those who “threaten the public with their asocial behavior”. This “preventive detention” was the official legal basis for imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps.6 According to the relevant definition, “asocial” was a person who even if not by “criminal behavior directed against the community, indicates that he does not intend to join the community”. This very vague definition thus allowed the persecution of hundreds of men and women, who were imprisoned in various detention and concentration camps without a court order.

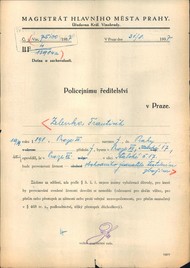

The regulation No. 89/42 Sb. defined “gypsies and gypsy nomads” as “asocials” and contained “special provisions on gypsies”: “Gypsies and people living in agypsy way of life” were forbidden to leave their officially assigned place of residence without prior permission of the Center for criminal investigation in Prague.

The Center for criminal investigation in Prague was established during the alignment and integration of the Protectorate’s authorities into the Reich’s structure and was the unit responsible for the execution of the all measurements against “gypsies”. Until its effective establishment the Criminal department of the police headquarters in Prague were to fulfil the Center’s tasks.7 The Center was the only authority eligible to issue travellers‘ ID cards. Travellers‘ ID cards issued by other authorities expired and were to be confiscated from their holders. The Center was also the only authority having the right to decide on the issuance of a license to operate a trade in a “wandering way”.8

With effect from 1 January 1942, the disciplinary labor camps in Lety u Písku and Hodonín u Kunštátu were converted into detention camps. Further, “preventive detention” in the Protectorate could be conducted in the coercive workhouses in Prague-Ruzyně, Pardubice and Brno (with a branch in Olšovec). The worst option for those subjected to this measure was deportation to the Auschwitz I concentration camp, later also to the Buchenwald and Ravensbrück concentration camps. Among the several hundred people who were deported from the Protectorate from April 1942 to February 1944 as “asocials”, there were only a few Roma.9 Although the racial ideology of the Nazis linked Roma and Sinti to “asocials”, they did not equate these groups.

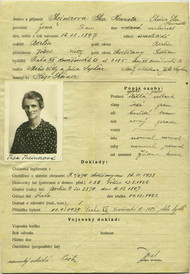

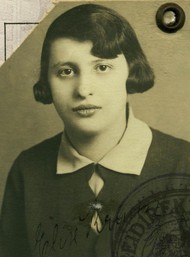

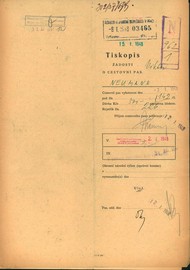

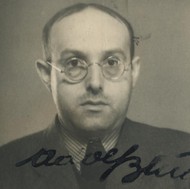

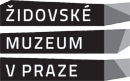

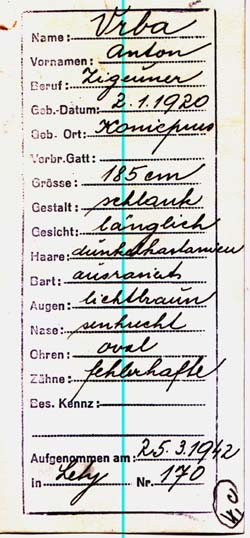

Ill. 2: Police identification card of Antonín Vrba, a prisoner of the detention camp in Lety u Písku, who was labelled as “asocial” by the protectorate authorities and subsequently imprisoned on 25 March 1942.

Next chapter: The "Gypsy"-census (August 2, 1942)