The Nazi persecution of Jews is most known about, but there were other groups that were persecuted, imprisoned, and killed, whether it be Roma and Sinti, people with disabilities, political prisoners, and yes, queer people.

Queer men were persecuted under Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, dating back to 1871. This article criminalized sexual acts between men and was used to persecute gay men, imprison them, and often, put them to death. Various Gestapo decrees and police orders enabled persecution of queer people without the need for a formal legal process. In fact, even after the war, and liberation by the Allies, this paragraph existed in the German Criminal Code in various forms until 1994, when it was finally abolished. During World War II between 5 000 and 15 000 men, persecuted under Paragraph 175 were sent to concentration camps.

While Paragraph 175 did not explicitly target lesbians, they too have been persecuted during the war. Unable to continue their lives, many, such as Elli Smula and Margarete Rosenberg, were deported and interred. In Austria, the penile code from 1852, Paragraph 129 criminalized all same sex relations. This was not amended in the Anschluss and was extended to the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia after 1939. The paragraph allowed prosecution, persecution, and deportation of all queer people.

In Nazi concentration camps, prisoners were marked with badges sewn onto their clothing. These denoted what they were imprisoned for, and marked how they were classified by their captors. Jewish prisoners wore the yellow Star of David. Political prisoners wore a red triangle. A pink triangle marked homosexual men persecuted under Paragraph 175. There were many other badges, denoting other categories too. Lesbian prisoners were in the black triangle category, which they shared with Roma and Sinti, mentally ill, vagrants, and others.

Men with pink triangle badges were likely to be at the bottom of camp hierarchy and were abused and ostracized not only by the capos, but by other prisoners too. Their chance of surviving imprisonment in concentration camps was very low.

There are many struggles in being able to document the stories of queer victims of the Holocaust. Our ability to hear stories and remember and commemorate people for their struggles and experience with persecution is given by the political climate. Initially, it was difficult even for Jewish survivors to speak about their experiences, as the socialist regime too was antisemitic, and was willing to acknowledge mostly the political prisoners. After the fall of USSR and restoration of democracy in Europe, it was finally possible for Jewish survivors of the Holocaust to speak up, and we were able to hear and document their stories, a living memory. However, queerness remained stigmatized, and by the time it became safe to come out in modern society, let alone to speak out about experiences during the war, queer survivors were far too few, as many have since died of old age. Recognition of queer victims came too late for most survivors to share their stories.

Historian Anna Hájková deals with the aspect of queer desire in her book "People Without History are Dust". She addresses the biases of the era when queer stories of people who experienced the Holocaust were collected, as well as the biases of the interviewers, or eyewitnesses. Irene Miller, in her interview with the Jewish Family and Children’s Services wanted to disclose her orientation, but because her queerness did not align with the specific values of the interviewer, this was dismissed, and her testimony was left devoid of any references to her partner, and the experiences that were the direct result of her being lesbian. t was only through a later interview, in which the interviewer came out to Miller as lesbian, that she was able to talk about her own queerness in her own terms. In connection with the testimonies of survivors, Hájková refers to the inherent homophobic tone in the testimonies, but also to the homophobia of the interviewers, which often also influenced the conversation. Queerness was often seen as threatening and dangerous by the contemporary witnesses, who, for example, constructed an image of a monstrous, terrifying lesbian who threatened the non-queer female prisoners.

While the uniqueness of Theresienstadt ghetto, one of the few camps, where men and women were not separated provides an invaluable testimony to the fact that homosexual relationships weren’t simply the result of lack of members of the opposite sex, but an innate preference. Queer desire cannot be explained purely by the absence of heterosexual possibilities. Unfortunately, it also best illustrates the erasure of queer victims and their stories. At the time, queerness was perceived as deviant and thus removed from the historical narrative. An example of this is a story of a female carer in youth welfare who loved another woman, who is mentioned in a diary entry by Egon Redlich (aka Gonda). This mention was deleted from the edited version of Gonda’s diary, as well as from the English edition of it, removing her story not once, but twice.

There is only one known and documented story of a trans person in Theresienstadt, Hambo. Based on recent research, this shows the Nazis knew about the existence of trans people, but also persecuted them.

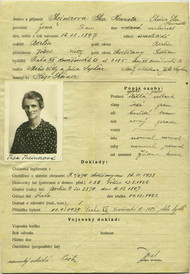

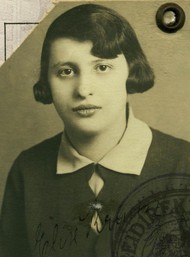

Hambo was born in 1907 into a Jewish household in Berlin, trained as a singer and worked as a clown and female impersonator. Attacked by the SA in 1933, they fled to Denmark, from where they were deported to Theresienstadt with another 500 Danish Jews. In the Theresienstadt ghetto, they became a popular figure in cultural life and took part in many performances and cabarets. In a diary entry by Ralph Oppenhejm, Hambo was described in a derogatory manner, and at the same time Oppenhejm speculated that Hambo earned extra portions of food through sex work. According to Hájková, this speculation was either an indication of queer sex work in the ghetto or simply an attempt at slander. Hambo survived the Holocaust and settled in Denmark, but little is known about their story.

To sum up the obstacles in researching and remembering queer stories from the Holocaust, and ensuring a more holistic narrative and understanding of persecution by the Nazis during WWII were given by heteronormative power structures and prejudice against “deviance”.

Czechoslovakia was progressive for its time, decriminalizing gay sex in 1961, but as mentioned, in Germany, Paragraph 175 stayed in place until mid-90s. With that in mind, criminal and stigmatized are two separate things, and even today, almost 80 years after the end of WWII, 40 countries around the world criminalize homosexuality, with 13 having a death penalty for this “offence”. And, in many places, the stigma remains today.

Despite these obstacles, we do have stories of people who survived the Holocaust and were able to tell their stories. Other than the examples mentioned above, you can read about the first-hand account of his 5 years of imprisonment for homosexuality of Josef Kohout, an Austrian, arrested under the Austrian equivalent of Paragraph 175. His story was written up by his friend, under the pseudonym Heinz Heger, and you can read his story in the book, The Men with the Pink Triangle. Josef came from a Catholic family and was imprisoned purely based on his sexuality.

However, there is a lot of intersectionality, which makes it more difficult to know just how many queer people were persecuted, and to hear their personal stories. Jews were persecuted regardless of their sexuality. If you were Jewish and queer, even if you’ve already been imprisoned, it was safer to stay closeted. As mentioned above, since queerness was considered deviant, it was punished, and you were likely to be ostracized even by your fellow prisoners.

Gerhard “Gad” Beck was a German of mixed Jewish ancestry. He managed to avoid imprisonment for a long time, helping organize underground effort to supply Jews who were trying to escape to Switzerland with food and hiding places. His boyfriend, Manfred Lewin, was not so lucky, and was arrested. Beck attempted to rescue him in 1942, but Lewin, trying to protect his family, refused to leave. Him and his entire family died in Auschwitz. In 1945, Beck was betrayed, and arrested by the Gestapo. He managed to survive the war, and in 2000, together with other gay Holocaust survivors, was featured in HBO’s document, Paragraph 175. You can also read his autobiography, published in 1995, called An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin.

Fredy Hirsch is one of the few exceptions, in that his story as an openly gay Jewish man is known. Born in Germany, and living in Prague, Czechoslovakia during the occupation, he was an athlete, a sports teacher, and an activist. In 1939, he managed to orchestrate the emigration to Denmark of 18 of his trainees, and thus, save them from deportation. However, he had no such luck himself, and was later deported to Auschwitz. Even though Rudolf Vrba warned him of the imminent liquidation of the Terezin Family Camp of BIIb, he refused to leave without the children he oversaw, and of whom he was protective of. He died on March 8, 1944, under strange circumstances. Today, he is one of the few gay victims of the Holocaust whose story we know, as he worked with and protected children and teenagers who lived long enough to save his memory and tell his story.

There are other mentions, and other stories if you search for them. But you must search for them.

In commemorating the Holocaust, we must be inclusive and consider all victims. Today, let us remember those who were queer. It was only in 1987 that the first memorial commemorating queer victims of the Holocaust was erected. The Homomonument can be found in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, right in front of the Anne Frank House on the Westermarkt. Stop by the Homomonument when you visit the house where Anne Frank hid during the war before her hiding place was discovered and she and her entire family were deported. After all, Anne also shared her fascination with the female body and her platonic love for her best friend in her diary. And so, she deserves a mention in this article.

Even today, queer people do not have equal rights in many places in the world. Not even here, in Czech Republic. While gay people can enter a registered partnership in the Czech Republic, they cannot be legally married, and some rights are withheld from them. Six of the countries in the European Union, including our neighbour, Slovakia, do not enable a registered partnership either. In fact, in 2022, Bratislava experienced a terrorist attack on the queer community by a shooter, who published a manifesto, talking about the superiority of the “white race” and blaming “Jewish LGBT+ agenda” for everything that’s wrong. Returning faces to queer victims of the Holocaust, and remembering their stories is important. Humanizing people who were persecuted purely for who they are is important. Because only through learning and understanding our history can we prevent similar atrocities in the future.

Due to heteronormative power structures, as a result, with few exceptions, there is a gap in the archives on queer fates during the Holocaust or, if such stories exist, they are assumed to be a deviation from heteronormative Holocaust studies.