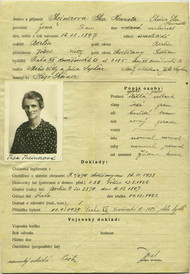

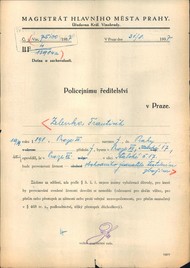

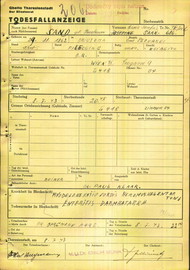

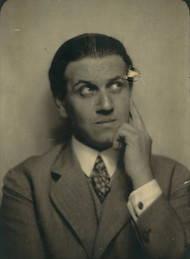

On 24 November 1941, at five in the morning, a group of 342 young Jewish people left Prague for Terezín. The first transport to the Terezín ghetto, still in the process of being built, was labelled the Aufbaukommando (the construction commando,

abbreviated to AK I. Those who gathered at Hybernská station included qualified workers - welders, carpenters, electricians, masons, stove-builders and bakers - with rucksacks in which they had been ordered to pack only personal items, food for a few days and a blanket. The task of this labour unit was to make the necessary adaptations to the existing barracks and other buildings at Terezín, a garrison town in the north of the Protectorate that was soon to hold the thousands of Jews who were transported to the newly-created ghetto. In Prague, the AK I men were told that they would be able to move freely and to visit their families at the weekends. In practice, soon after their arrival they became the ghetto's first prisoners.

In summer 1941 a division called G (ghetto) was formed within the Prague Jewish Community, its task being to draw up a plan for the creation of a Jewish labour camp in the Protectorate. Terezín does not appear in the G division's documentation as one of the possible locations until November 1941. Although the leaders of the Jewish community had reservations about the place, and fears concerning its fortress character, Terezín was the Germans' final choice. The barracks were suitable for mass accommodation, while the town's ramparts and fortifications made it easy to isolate from the outside world. In addition, there was a railway station two and a half kilometres away.

Members of the AK were imprisoned in one of the dilapidated barracks buildings, furnished with only a few broken beds, a couple of tables and some benches. Former stables, empty storerooms and other areas that had never been used as living quarters were now converted into dormitories, often badly-lit and with no chance of being heated to a bearable temperature. In her book Jakob Edelstein, Ruth Bondy writes of the Aufbaukommando's arrival: (...) the vanguard (...) found the Sudeten Barracks (...) empty and dirty (...). On the ground floor were stables, storerooms, toilets, primitive showers and two dark, entirely unequipped kitchens (...) There were piles of rubbish in the stables, and the damp, bare concrete floor was dirty. The first arrivals lay on it in the freezing December nights, with no mattresses, without even a bit of straw, just their rucksacks under their heads and the water dripping from the ceiling. Despite their promises, the Germans brought no food. The new arrivals lived off the supplies they had brought from home, and suffered ever-greater hunger.

(pp. 248-249)

The members of the construction commando

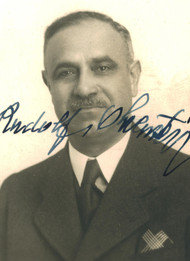

arrived in Terezín, and was given similar tasks to the members of the first group. On 4 December the twenty-two-person Council of Elders arrived, headed by Jakob Edelstein.

Further transports followed, and by the end of 1941 there were eight thousand prisoners in the ill-prepared dormitories of the Terezín camp. The original civilian inhabitants, who did not leave Terezín until the end of June 1942, were not allowed to make contact with any of the deported Jews. Before long, a number of bans were imposed: no walking on the pavements, buying anything in the shops, whistling or singing and so on. The Jews in Terezín were guarded by six hundred Czech policemen, in three shifts. Any illusion of a bearable and productive Jewish town with its own administration had vanished for good. The Jews transported in AK I and II were promised many advantages, but these were gradually taken away. Then the most significant privilege given to members of the construction commando,

protection against transport to the east, ceased to function in 1944, and most of them were deported to Auschwitz. Of the 342 young and healthy men deported to Terezín on 24 November 1941, only 86 survived until liberation.

-

See also:

-

Review of Jiří Kosta's book: Život mezi úzkostí a nadějí (Life Between Anxiety and Hope) (In Czech)

-

Extract from Jiří Kosta's book: Život mezi úzkostí a nadějí (Life Between Anxiety and Hope) (In Czech).

-

Literature:

-

Adler, Hans G. Terezín 1941-1945. Tvář nuceného společenství (Terezín 1941-1945. The Face of a Forced Community). Praha: Barrister&Principal, 2003. 380 s.

-

Bondyová, Ruth. Jakob Edelstein. Praha: Sefer, 2001. 487 s.

-

Franková, Anita. Přípravy ke koncentraci protektorátních židů. Předhistorie terezínského ghetta (Preparations for the concentration of Protectorate Jews. "Prehistory" of Terezín ghetto). Terezínské studie a dokumenty. s. 29-50.