Arrival

Trains with the deportees arrived day and night at the Auschwitz station. After the train stopped and the wagons opened, they had to disembark immediately under the supervision of armed SS guards with dogs. Everything took place at a very fast pace and was accompanied by the screams of people and the barking of dogs. The frightened men and women, together with their crying children, were loaded onto trucks, which were perpared for their further transport, or they had to lined up in rows of five people and walk to their destination. From the spring of 1944, the railway tracks lead directly into the camp.

Survivor Aloisie Blumaierová, née Ištvánová (born 1926 in Bořitov, prisoners number Z-1199) recalled her arrival: „We arrived in Auschwitz in the afternoon, it was still light. The SS and the dogs immediately drove us out of the wagons and we had to set out on foot for the next journey. It didn't take long, maybe thirty minutes. Coming into that environment was terrible. Only barbed wire everywhere and behind them one barrack building after another.“1

Upon arrival at the camp, the admission process, consisting of several phases, took place immediately. The first phased consisted

of a shared bath in the so-called sauna under showers or in washrooms. The humiliating joint shower took place in the presence

of mocking SS guards and prison officials with constant swearing, beatings, and bullying. In addition, the guards alternated

hot and ice water with no warning. Then the prisoners` hair was completely shaved off. Some already arrived with cut hair

from, for example, other internment and concentration camps (e.g., transports from the protectorate's “gypsy camp” in Hodonín

u Kunštátu).

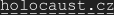

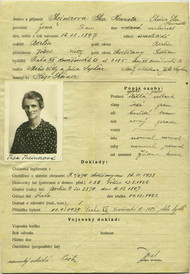

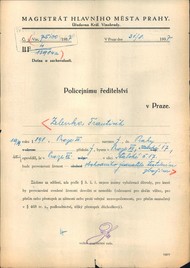

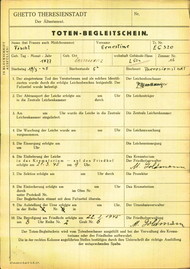

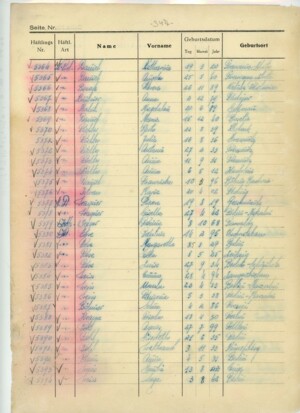

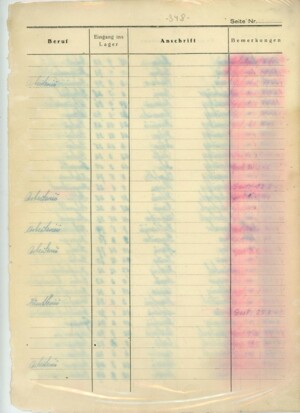

A page taken from the record book of women imprisoned in the "gypsy camp" of Auschwitz-Birkenau. (picture: Archive of the State museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau).

Antonín Absolon-Růžička (born 1930 in Mistřín, prisoners number Z-7539) recalled: „In the morning we were lined up, we had to keep our things in the block, and they took us back to the neighboring camp. There was a large room in the barracks where we all had to undress. That was awful. People didn't want to undress because they were all there together, men, women“„, and children. There was screaming, beating, crying. I remember well that my oldest sister, Božena, who was 16 years old, did not want to undress, even though a lot of people were already naked. An SS-man beat her, ripped her clothes off, my sister was screaming, crying, and defending herself. We had to tie our clothes together, so that the number was visible. Then we were completely cut and shaved. We didn't recognize ourselves, the way we looked afterwards.“2

The “bath” was followed by getting dressed. Due to the lack of prison clothing, people imprisoned in the “gypsy camp”, different from the prisoners in other parts of the Auschwitz complex, were not given special prison clothes or shoes after their arrival in the camp. Some of the newcomers were left in the clothes and shoes in which they arrived, others were fitted with clothes after the gassed, especially Jewish, prisoners. In both cases, long stripes in the form of the letter X were painted in red oil on the entire back of these civilian garments.

Tomáš Šubrt (born 1901 in Čeložnice, prisoners number Z-4751) said: „They left us our civilian clothes, but they painted a red cross on our clothes, on our caps and hats, so that they could find us everywhere if we ran away. We wore that clothing about 9 months, before we tore it apart. Then, we didn't have shoes or clothes and we had to walk barefoot and half-naked. When a transport arrived, and there were many of them every day, they were Poles, Czechs, Russians, French, they stripped them, gave them prison clothes and gave us as gypsies their civilian clothed, but dyed, marked.“3

The initial cleansing was followed by the registration of prisoners. Each received a strip of white canvas, which he had to wear sewn on the garment in the left half of his chest, and the men also on the outer seam of his right leg trousers. There were three symbols on the canvas: a triangle, a letter, and a number. The triangle was a tag every prisoner was given, its color expressed the prisoner’s category. Roma and Sinti were classified by the Nazis generally as “asocials” and received black triangles, regardless of their previous social status, property they might have owned and cultural conditions. The prison number replaced the name of each prisoner throughout his internment. The numbering was done in several series, differentiated with letters of the capital alphabet and people imprisoned in the “Gypsy camp” were given numbers from the Z-series (“Z” as abbreviation of the German word “Zigeuner”, i.e. gypsy).

People imprisoned in the Auschwitz camp complex have also been tattooed since the spring of 1943 due to high mortality, difficulties in recognizing the dead and to render escape impossible. Prisoner functionaries tattooed the prisoner’s number on the legs of Romani children and on the left forearms other Romani women and men. Růžena Otáhalová, née Krausová (born 1928 in Dolní Cerekev, prisoners number Z-1781) remembered: „They drove us into a big hall, we fell over each other, they tore the little children away from their parents, so they started looking for each other. We were there overnight without food, without everything, then I found my mother there. Here they also started tattooing us, with that one needle they tattooed us until it broke, no exchange. Then we had terrible sores because everyone had different blood.“4

Accommodation and hygienic conditions

After all the necessary admission procedures, the imprisoned people were accommodated. Unlike in other parts of Auschwitz, in the “gypsy family camp” and the “Terezín family camp”, there was no normal division of families, resp. separation of men and women. Regarding Roma and Sinti, the reasons for this form of internment were probably based on the racial ideology of the Nazis. At the same time, the “gypsy family camp” could serve as a space for gaining experience in the liquidation of other groups of the population.5

The wooden residential block or barracks with an area of 389 m2 was adapted to accommodate 300 people, but immediately after the opening of the camp, up to 1,000 to 1,200 people were crammed into one block and the accommodation capacity was significantly exceeded. The individual floors of the three-story wooden bays (slang. bukša), which were built along the longer inner walls of the barracks, were planned as a sleeping place for five people, in fact, fifteen people had to sleep there. Officially, they were supposed to sleep on wood wool straw mats, but usually there were none, so people slept on the bare boards and covered themselves with blankets only.

The only interior of the barracks were two tin stoves, which stood at both sides of each block and were connected by a brick channel that ran across the floor. Together, they were supposed to function as a heating for the whole barrack. Since they were not used for this purpose, the brick wall was used in other ways (prisoner functionaries used it to distribute food rations, the prisoners sat there and stored their personal belongings on it).

The blocks were poorly lit and ventilated only by small air shafts and open gates during the day which caused darkness and bad air throughout the day, the situation deteriorated even more at night after the gate closed. The roofs were leaking, since the barracks were built without any insulation and, similarly, as there was no floor covering, the mud the barracks were built on stayed moist.

The hygienic conditions in the camp were appalling. Water was never introduced into the house huts for washing, and instead of toilets, only barrels stood at the back door, which usually overflowed. The overcrowding of the barracks and the general lack of water (so-called sauna washrooms functioned only to a limited extent for prisoners) made proper personal hygiene impossible just as cleaning. Because of this, the prisoners themselves had no chance but to be dirty, and the same applied to their clothes and blankets. Therefore, insects (especially clothes lice and scabies) spread throughout the camp, making it impossible for the prisoners to rest and, additionally, transmitted various diseases. The non-systematic attempts to remove lice couldn't solve this problem.

Nutrition

After a short stay in the camp, the imprisoned people began to feel a lasting hunger and thirst that accompanied them everywhere. The prisoners were to receive food in the morning, at noon, and in the evening, but none of the rations met the prescribed, albeit low, standards. Responsible for this was the poor storage and disposal of rotten food, shortcomings in the technical equipment of kitchens, but above all theft, committed by the power apparatus, but also by other prisoners led by their own hunger and instinct of self-preservation.

Marie Nedvědová, née Kovářová (born in 1923 in Bedlno, Rakovník district, prisoners number unknown) recalled: „We received food once a day, and it was bad food. In addition, fodder beets in small portions and 10 slices of bread. We had tea from birch leaves and we didn't see coffee the whole time we were there.“6

Only the small number of those, who brought money or gold to the camp and prominent people, that means, all those who held positions as prisoner functionaries or obtained permanent work in one of the various camp facilities, had the opportunity to supplement the insufficient ration of food through purchases in the canteen with a very limited selection and on the black market. However, most prisoners suffered from constant hunger, which turned into long-term malnutrition and gradually exhausted the body. In desperation and under threat of punishment, some prisoners went to the camp kitchens to pick up leftovers from weaned barrels for food or to search piles of carried kitchen rubbish. Some also collected and ate roots, stems and leaves in the camp area.

Forced labour

All men and women in the “gypsy camp” had to work, so long as they could. A small number of prisoners were selected for permanent work in kitchens, hospitals, and other camp facilities, which allowed them to obtain better accommodation and food conditions, and thus a greater chance of survival. Most prisoners though did not have any work benefits, as they worked very little and only occasionally. Men and women were deployed for particularly demanding construction work (construction of toilets, washrooms or showers, camp roads, digging of drainage ditches, groundwork between barracks and in the camp surroundings, etc.) or were forced to conduct various pointless tasks (carrying heavy loads from one place to another and back, digging up turf or clay, shifting piles of sand and stones). Occasionally, and mostly for males, there was work outside the camp, like extending the railway ramp or groundworks near the completed crematoria, groups of women, among other tasks, had to collect nettles and other herbs for the camp kitchens.

Some work group leaders, kapos and their assistants, who were armed with sticks or batons, treated their fellow prisoners ruthlessly and cruelly, which the SS often forced them to do under threat of their own punishment. Prisoners who could not keep up with the set pace were beaten, which, in combination with their physical exhaustion, sometimes led to their death.

František Holomek (born 1918 in Veselí nad Moravou, prisoners number Z-1208) recalled working in the camp as follows: „… we worked on the roads, we repaired the roads. We were digging. They beat us at work, people died like flies. We were not even allowed to stand up, whenever we stood up, we got beaten. My wife's grandfather also arrived there. He was older. One time, when he didn`t do anything, and they caught him, they beat him and that was the end. The corpses were piled up, cars arrived in the evening, and they were put in the incinerator.“7

One way to get out of the “gypsy camp” was to be transferred to work in another part of the Auschwitz complex or to be deported to another concentration camp. But also, there, thousands of people fell victim to the method of "liquidation by work" or various pseudo-medical experiments (e.g., forced sterilization of women in the Ravensbrück concentration camp). However, the transfers of prisoners from the "gypsy camp" motivated by the Nazis need for labor, was an option mainly for young, healthy and physically fit individuals, and took place continuously throughout its operation. As early as March 4 and 12, 1943, about 700 men and boys were transferred to work in the Auschwitz I concentration camp, and on November 9, 1943, about 100 men were deported further to the Natzweiler concentration camp. During spring and summer of 1944, several transports with a total of 3,000 men and women were deployed for work in the Buchenwald, Ravensbrück and Flossenbürg concentration camps. However, not all of them endured the hard work and if, after some time, they were classified as unfit for work, they were sent back to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Camp regime and penalties

The everyday life in the camp was determined mainly by the observance of the strict provisions of the unwritten camp rules or sadistic regulations that were set up informally. Around four o'clock in the morning, the day at the camp began with gong strikes that announced the wake-up call. While getting up, the prisoners were accompanied by SS-guards and kapos shouting at them, beating, and harassing them, pushing those who were still asleep out of their beds, pouring cold water over them, pulling their hair, etc. Inside the barracks, inhabited by several hundred people, there was only minimal space and possibility to get dressed quickly or some personal hygiene. Still, just the slightest disorder was punished on the spot. If children had urinated or defecated at night, their parents were punished.

After quickly leaving the barracks, there was little time left to queue up for the opportunity to perform a bodily need and a basic cleansing. Any delay carried the risk for each prisoner, that upon his return to the barrack, someone else would have taken his food ration. The short breakfast was followed by a morning call. The prisoners had to stand in front of their barracks in rows of ten in order to facilitate their counting. Regardless of the weather, they had to remain in line until the exact sum of those present, those who died at night, were transferred to other blocks or had been deported further to other camps, matched the number counted.

Aloisie Blumaierová, née Ištvánová (born 1926 in Bořitov, Blansko district, prisoners number Z-1199) recalled: „From day one, we had to submit to a tough camp regime that began with a roll call. In the morning we had to stand in rows in front of the block and everyone had to report their number. Doctors reported the numbers of the sick, mothers had to report the numbers of their younger children. And if it didn`t match, the whole ceremony was repeated. The roll call lasted until everyone was counted.“8

After the roll call, old people and initially also women with small children returned to the barracks. Later, the children were placed in a so-called kindergarten and a nursery for the whole day. All other prisoners were to work from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. After returning from work, the evening roll calls followed, which were endless, especially when one of the prisoners was missing or had tried to escape. In this case, the roll call lasted until the SS-guards managed to catch the escaped prisoner and brought him back to the camp.

The roll call was followed by dinner and free time, at least if there was time left and no punishments took place and no delousing or other activities were ordered. During this small amount of free time, the prisoners gathered around the barracks, where they talked to each other, sold, or exchanged things or visited each other in their respective barracks. Some of the prisoners played musical instruments or sang. The “gypsy camp” is also the place of origin of several songs whose lyrics in Romani describe the miserable life in the camp (e.g., Labesbryku, éj, Osvěnčinatar amen dine: from Auschwitz we were taken to Ravensbrück). One of these so-called plaintive songs is “Aušvicate hi kher baro” (There is a big house in Auschwitz). The song did not have a stable shape and the prisoners sang it in various variants, which were recorded in Poland, Slovakia, and Moravia after the war. Růžena Danielová (1904‒1988, prisoners number Z-8259) from Moravian village Mutěnice, who survived her internment as the only one from her family also carried with her one of the versions from the “gypsy camp”. The lyrics and melodies of the song have become one of the musical symbols of the suffering of the Roma in Auschwitz and are often part of various commemorative events, not only in the Czech Republic.9

At 9 p.m., gong strikes announced the curfew, during which it was strictly forbidden to leave the barracks. Prisoners who violated this ban, were tracked down by searchlights, and shot by the SS-guards on the watch towers.

The executive power in the camp was the so-called prisoners` self-administration, which was subordinate to the military structure of the SS. Members of the prisoners` self-administration, who were recruited into the "gypsy camp" from the ranks of non-Roma prisoners, wore ribbons (Binde) on their sleeves, indicating their function and rank. Black ribbons marked the prisoner functionaries with the greatest power and advantages, which were the elder of the camp (Lagerältester), the administration clerk (Rapportschreiber) and the head of Kapos (Lagerkapo). Elders of the block (Blockältester, slang. Block, blocker), who were responsible for order and cleanliness in their barracks, for allocating food and clothing, controlling the presence of all prisoners, etc. wore red ribbons. Their deputies (Vertreter), block clerks (Blockschreiber) and prisoners with corresponding tasks (Stubendienst, slang. štubový, štubinista) supported them. The officials responsible for the work results of the individual working groups were hierarchized as kapo (Kapo), sub-kapo (Unterkapo) and foremen (Vorarbeiter) and wore yellow ribbons. Members of the prisoners` self-administration had various advantages in the camp, e.g., they were exempted from physical work, lived separately in small rooms in their blocks, received more food, were relatively clean and well dressed, etc. On the other hand, they were often bullied and punished by the SS if they failed to conduct their assigned tasks according to the wishes of the SS, such as order on the blocks, etc.

The management of the camp, through subordinates and the prisoners` self-administration, severely and cruelly punished real and imaginary offenses committed by prisoners. The most common group punishment, pack drill (Strafexerzieren, slang. Sport), was carried out at the end of the camp road littered with sharp gravel. Another common punishment was additional work (Strafarbeit), that had to be conducted during free time, ie on Sundays and public holidays, during lunch breaks or after the end of the evening roll call and during the night. Withdrawal of (parts of the) food rations (Kostenzug) while one had to keep on working was a punishment prisoners feared particularly. Among the individual punishments, the most common was beating, which was carried out on a special bench at the guardhouse or directly in front of the fellow prisoners. It was also common to tie a prisoner with rope or chain to the ceiling beams in the barracks with their hands behind the back, just high enough for them not to be able to stand on their own feet anymore (Pfahlbinden).

Another possibility punishment was detention in the camp prison located in block 11 of the Auschwitz I concentration camp, next to the execution site. There, prisoners were imprisoned in a so-called bunker, where there were also dark cells. The camp Gestapo also placed prisoners in the so-called criminal command (Strafkommando), whose members were under strict supervision, received lower food rations and worked in particularly difficult workplaces.

Escape

Besides being transferred to another part of the Auschwitz complex or another concentration camp for work, the only chance for people imprisoned in the "gypsy camp" to rescue themselves was trying to escape. Escaping from the camp though was mostly unsuccessful, as the prisoners had to cross the heavily guarded and barbed-wire-enclosed space that surrounded the “gypsy camp” and all other camps next to it, since they rarely worked outside the camp. Despite these unfavorable circumstances, some of the Roma and Sinti were willing to take the risk and tried to escape. According to the incomplete records in the bunker book, i.e., the prison of the Auschwitz complex, over forty people from the “gypsy camp” tried to escape. The very first report of escape from this camp notes that the Polish prisoner Stefanie Ciuroń (unknown prisoners number) fled on April 7, 1943. The second woman who escaped was Weronika Walansewicz (prisoners number Z-9611). She fled on February 6, 1944. Both were not captured and their fates are unknown.

The camp documentation also contains records of escapes by Roma from the Czech lands, though all of them failed. On May 4, 1943, Josef Serinek and František Růžička fled. Another six Czech Roma who fled on May 7, 1943, were subsequently captured and shot on May 22, 1943 by an execution squad. Jaroslav Herák (Z-4466) from Luhačovice even managed to escape twice. He first attempt on November 27, 1943, ended in capture and detention, later he was released from the camp prison and placed in the criminal command. From there, he tried to escape again on February 1, 1944. He fled with several others, but they were captured and executed on the run.10

Marie Nedvědová, née Kovářová (born in 1923 in Bedlno, Rakovník district, unknown prisoners number) recalled: „When a prisoner escaped, it was something terrible, the whole block was shut down and we couldn't even go out. There were drawn wires and there was electricity. The fugitive was shot and then shown around in the barracks, for us to know how we would end up if we also tried to run away.“11

The attempts of escape undertaken by Roma and Sinti from the "gypsy camp" mostly ended in failure, and although all the other imprisoned people in the camp knew this, it did not stop everyone from trying. Under these circumstances, an attempt to escape was a manifestation of deep despair, as well as courage and resistance against violence and a natural protest of individuals against the power in charge.

Sickness and death

The catastrophic conditions concerning nutrition, accommodation and hygiene the “gypsy camp” quickly exhausted the imprisoned people and weakened their resistance to diseases, which became the main cause of mass mortality, given that health care was almost nonexistent, too. Morbidity and mortality culminated mainly in the summer of 1943 and then again in the winter of 1943-1944. A total of about 19,300 people died in the camp, including about 4,300 people murdered during the night of August 2-3, 1944, which counts up to 84% of all people imprisoned in the “gypsy camp”.12

Zdeněk Daňhel (born 1928 in Bílovice, Z-1255) remembered: „We did not have access to water. We secretly went to the wells, let down some jar on a string, and drank the water drawn in this way. It was forbidden, because the water was contaminated. Later, typhus and other diseases occurred. Children died, the elderly and others, up to 50 people a day.“13

The camp hospital (Häftlingskrankenbau), called the “Revier”, was in charge of the very limited health care available for the prisoners, and was only established by the end of March 1943, when around 10,000 people were already living in the “gypsy camp”. It originally consisted of two, later, due to the enormous increase in the number of patients of six wooden barracks. The hospital's facilities were almost non-existent in the first weeks of the camp's existence. Patients, of whom there were up to 2,000 in the Revier at during the worst times, lay on three-story wooden bunk beds, the same as in the barracks. On bunk bed measuring 1.85 x 2.8m had to accomodate four to five, often even more patients. The initial number of 200 patients in one block soon increased to 400 to 800 people in the early summer of 1943. Patients were allocated to different barracks according to the diseases they suffered.

SS-physicians were in charge of the hospital, for the longest time Dr. Josef Mengele held this function. His assistants were SS-paramedics, the so-called SDG (Sanitätsdienstgrad). The highest prisoners functionary here was the hospital elder (Revierältester), most of them were no trained doctors. Under the supervision of SS-doctors, the actual medical service was performed by prisoner doctors. However, their ability to help the sick was very limited, as there was a lack of water, medicine, hygiene, adequate nutrition, and no possibility for an adequate isolation of patients with infectious diseases. Untrained people from the ranks of Roma prisoners worked in the hospital as nurses, whose task was to distribute food and measure the temperatures of patients.

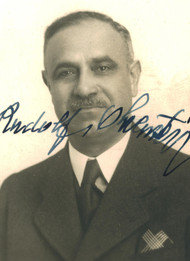

Two Czech Jewish prisoners were also among the prison doctors in the “gypsy camp”. Pediatrician prof. Dr. Berthold Epstein (1890-1962, prisoners number 79104) worked at the Medical Faculty of the German University in Prague, where he also headed the II. children's clinic and held a private practice. After the occupation of the Czech lands in 1939, he resigned from both positions and moved to Norway, where he was arrested in 1942 and deported to Auschwitz. Together with prof. Epstein also Dr. Rudolf Weisskopf-Vítek (born 1895, prisoners number 71261) worked at the hospital in the “gypsy camp”, who was a dermatovenerologist in Prague-Karlín before his internment.14

The most common diseases included diarrhea, which occurred because of poor nutrition and drinking contaminated water, as well as typhoid fever and spotted fever. Furthermore, scurvy, scabies, malaria, tuberculosis, dysentery and smallpox also spread uncontrollably in the “gypsy camp”. In addition, children and adolescents suffered from noma or water cancer, a disease caused by extreme malnutrition. The camp hospital had not enough space for everyone who got sick, so people died on the blocks. Due to the spreading epidemics, the health situation in the “gypsy camp” was so catastrophic that in May 1943, the reception of new transports had to be stopped for some time. The suspicion of typhus was also a pretext for the camp commander to order newly arrived prisoners directly into the gas chambers. In March 1943, about 1,700 Polish Roma from the “gypsy camp” in Szepetow were murdered without prior registration, in May 1943 more than a thousand people from Bialystok shared their fate.

Vlasta Serynková (born 1922 in Pilsen, prisoners number Z-7934) recalled: „There was a lot of typhus, scabies, tuberculosis in the camp. The prisoners had no medicine. We got injections, nobody knew what they were. Mortality was high. We left the dead on the block for three days and took their rations. After three days, we reported their deaths. My mother died in Auschwitz, she was burned, my sisters Anna and Antonia and eight children, and my brothers Karel and Eduard. My brother Eduard was beaten by the Germans because he could no longer work, because of hunger. Only one brother returned, Alois.“15

The most endangered group of people imprisoned in the “gypsy camp” were the children who came there with their parents and other relatives and those children, wo were born directly in the camp - initially in the barracks, from the end of March 1943 in the camp hospital. In total, about 370 children were born in the “gypsy camp” (among them about 60 with protectorate affiliation), but none of them survived.16 In the spring of 1943, a so-called kindergarten (Kindergarten) was established in the "gypsy camp" with a crèche for children under the age of six. Their mothers had to hand them over to the nurses after the morning roll call and picked them up only after returning from work in the afternoon. Later, orphaned children were permanently placed in the kindergarten, their number constantly increasing. In total, about 9,000 children under the age of 14 were imprisoned in the “gypsy camp” (i.e., about 39% of all people imprisoned in the "gypsy camp"), the vast majority did not survive the internment. Those who lived through the summer of 1944, were at least ten years of age and had a fitting physical appearance, Dr. Mengele selected for the last transport to the Buchenwald and Ravensbrūck concentration camps. Younger or sick children, along with the other remaining prisoners of the “gypsy camp”, were murdered in early August 1944 in the gas chambers.

Medical experiments

Many Nazi German scientists and physicians participated in the development of Nazi ideology with their research during and before World War II, concerning such topics as racial theories about the supremacy of the German nation, racial hygiene, etc. Their findings were then put into practice by other physicians, especially in concentration camps. There, SS doctors could use defenseless living people, especially Jewish and Roma prisoners, for their research and experiments that they otherwise would not have been able to carry out.17

In the “gypsy camp”, experiments on imprisoned people were carried out by SS doctor Dr. Josef Mengele and his subordinate assistants. Next to his general medical work, he was involved in race research from the beginning. He performed various anthropological and anthropometric measurements on Romani prisoners, but also medical experiments and experimental procedures, especially on young children and identical twins. Under Mengele's supervision, doctors also conducted research about noma, the causes of this disease and possible treatment. The Czech Jewish prisoner doctors prof. Berthold Epstein and Dr. Rudolf Weisskopf-Vítek were assigned this task. Other research undertaken at the Auschwitz concentration camp included attempts to develop a cheap method of sterilization, conducted by SS-doctors mainly on women but also on men. These experiments were mostly very painful and in many cases led to death.

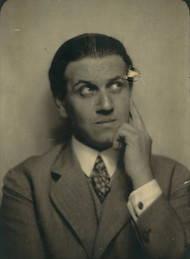

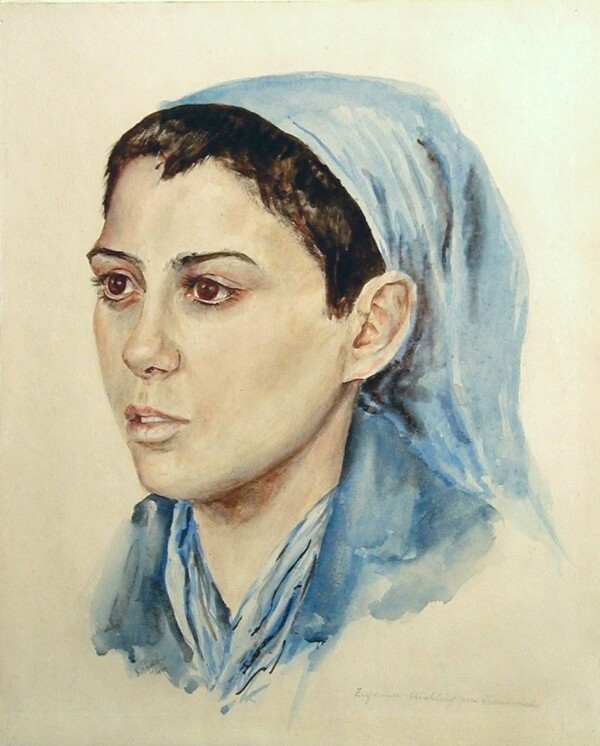

As part of the research of the “gypsy race” Dr. Mengele conducted, Jewish prisoner Annemarie "Dina" Gottlieb (1923‒2009, prisoners number 61016),

a native of Brno, who was deported from Terezín to the "Terezín family camp" in the B-II-b section of Auschwitz-Birkenau

in December 1943 had to draw portraits of selected men and women imprisoned in the “gypsy camp”. Until today, seven colorful

watercolor paintings have been preserved depicting unknown Romani and Sinti men and women from France, Germany and Poland.

These unique watercolor paintings are part of the collections of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Auschwitz.

Portrait of an unknown prisoner from France painted by Annemaria “Dina” Gottlieb in the “gypsy camp” in concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau for camp doctor Josef Mengele, 1944. (picture: Archive of the State museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau).